My family on my Dad's side were coalminers in the northern coalfields of NSW, with my Poppy working all his life as an underground miner and his father and uncle before him.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

or signup to continue reading

In addition to being an underground coal miner, my great grandfather was an avid boxer and his son, my great uncle Ad, was just starting out as a fighter in the 1920s. He had a fight coming up one Saturday and my great grandfather asked his brother, George Sneddon, if he could swap shifts at the Bellbird Colliery with him so he could be there. Of course, George said yes.

So, at 1pm, on Saturday, September 1, 1923, my great great uncle George went down the mine to begin his shift instead of his brother, my great grandfather, and an hour into the afternoon shift, every underground miner's worst fears were realised - a fire had broken out.

As a naturally combustible ore, coalminers - especially underground coalminers - are no strangers to extreme risks of safety, even now. However, a hundred years ago conditions were such that the risks taken on a daily basis, just by turning up to work, would give a modern safety manager heart palpitations.

Perhaps most staggering - particularly given the combustible nature of coal - was that naked flame safety lamps were in use at the site and miners often smoked cigarettes while on shift in the mine workings.

The Bellbird Mine Disaster is considered to be unparalleled in the history of the NSW coalfields. It occurred at a time where working conditions were very poor, safety protocols had yet to advance, emergency telephone lines were unreliable, and there were no organised, centralised mines rescue stations that would ensure a practised and coordinated response to mining disasters.

Subsequently the 20 workers who went down the mine on that fateful afternoon, plus one of the rescue team, perished, my great great uncle among them. He was 33 years old, married, and the father of six children. The following Monday, The Newcastle Herald shared the names, ages, marital status, occupation and location of residence of those who'd lost their lives, revealing that 38 children lost a parent and 16 women had been widowed. Despite the loss of 21 souls, only 15 were recovered immediately before the mine was sealed, entombing the remaining six.

Following the Bellbird Mine Disaster, inquests and a royal commission were formed to determine the cause of the fire and explosions that violently took the lives of the 21 men. While these investigations failed to determine a specific cause of the accident beyond assumptions and informed guess work, they did shine a spotlight on the need for reform in how things were done.

MORE ZOE WUNDENBERG:

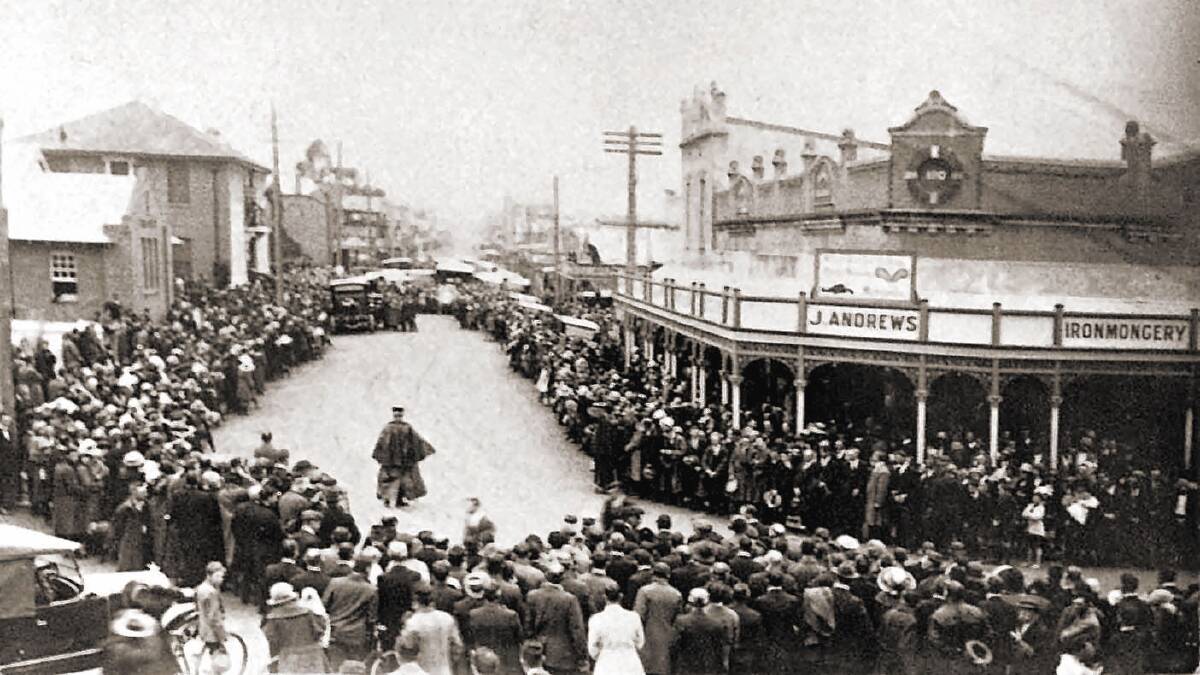

One hundred years have passed since the disaster, and yet the impact of it is still felt by the families, the locals and the mining industry. A sociologist undertook a study of the region revealing the Bellbird Mining Disaster had become a "landmark" in the area's history. The trauma of having to leave six of their fellow miners in the mine and seal it up to contain the fire and reduce the impact of the toxic gases and smoke only further cemented this tragedy in the local community, scarring its landscape with the horrors experienced by these workers. The volunteers that flocked to be a part of the rescue effort had overwhelmed, demonstrating the brotherhood born from this shared burden of the dangers of this work, but also the lack of a prepared, systematic approach to mines rescue that unions had been fighting for since the previous century.

The 100 year commemoration event, held in Cessnock on the weekend, saw the next generations of these men's families come back together to remember their sacrifice. My Dad met a long lost cousin - the grandson of George Sneddon - for the first time, people shared stories and memories, and reflected on the inter-generational grief stemming from this accident. It also renewed the appreciation for the changes that followed the Bellbird Mine Disaster, with the Mines Rescue Act (NSW) subsequently passing in 1925, to ensure that any future rescue efforts would be coordinated, planned, practised and centrally managed.

While tragic, and generationally impactful, the deaths of those 21 miners were not in vain. They made the industry ultimately safer and in doing so, have saved the lives of countless others.

- Zoë Wundenberg is a careers consultant and un/employment advocate at impressability.com.au, and a regular columnist for ACM.