Seventy-five years ago this week, prime minister Ben Chifley issued a 42-word press statement that told Australians his Labor government would nationalise Australia's private banks. It was among Chifley's most significant announcements and perhaps his gravest miscalculation.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

August 16 was a chilly winter Saturday and Australians were enjoying a typical weekend.

Apart from a few officials in Canberra and ministers called to an unscheduled cabinet meeting, no-one had any warning the government planned to impose state control on the nation's trading banks. The press statement stunned everyone.

In 1947 Australia had eight large trading banks, three of which were British-owned. They were worth close to a billion pounds and had operated in the country since colonial times.

Twenty-two thousand bank employees in branches around the country provided banking services to one in five Australians. Hidden behind the prime minister's abrupt announcement was a monumental undertaking. The government would nationalise the banking industry and make the Commonwealth Bank a monopoly. The bank would be unique in the English-speaking world because it would be both a central bank and a provider of services to the public. There was no Australian precedent for such a bold measure and few international examples outside the Soviet bloc. Furthermore, no one including Chifley knew how this would work. Yet after a boisterous passage through Parliament, the idea was law by Christmas.

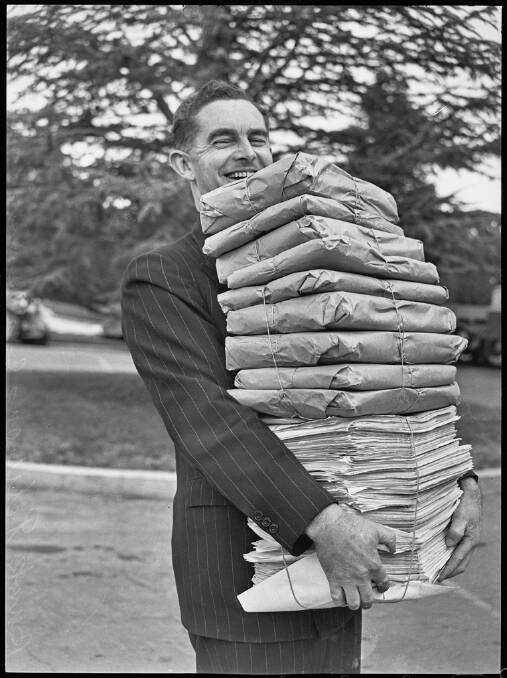

Ben Chifley's terse one-paragraph announcement generated thousands of negative newspaper stories, editorials, opinion pieces, columns, cartoons, letters, photos and ads.

Protest groups sprang up like mushrooms across the continent. There were rallies, town hall meetings, street marches, radio programs and the nation's mailboxes were stuffed with millions of bulletins, brochures, circulars, flyers, leaflets and pamphlets.

Unionists and ALP supporters applauded the idea. They recalled the financial hardships of the 1890s Depression, the Great Depression and two world wars. Though the government failed to provide any coherent explanation for weeks, the true believers sensed Chifley's logic. The best way to create the postwar social welfare system and an equitable economy was for the government to control the nation's credit.

They believed the bankers of Collins Street and Martin Place would never help Chifley usher in his promise of a golden age because the bankers and their boards were motivated purely by profit. Many more people saw the bank plan as an imprudent experiment to introduce socialism to Australia. Some said it reeked of Communism. They questioned whether insurance companies, radio stations and newspapers would be next once the Commonwealth abolished the banks.

Would it all end with bureaucrats supervising pie carts and hot dog stands?

The private banks fought back and spent untold millions on a media war, court challenges and a grassroots insurgency. Bank officers were encouraged to quit their tellers' cages and become political activists after hours and on weekends. The opposition leader Robert Menzies marched the Liberal Party to the front ranks of the protest movement and waged a political and mass media campaign to thwart a takeover.

For the next two years bank nationalisation was a contested issue in state elections and byelections. It got mixed into the 1948 referendum on prices and rents and was finally settled by the defeat of the Labor government in the 1949 election. It helped Menzies regain the prime ministership and send the Australian Labor Party into an electoral wilderness for almost a quarter century.

READ MORE:

Bank nationalisation was as raucous as any episode in Australian history and its twists and turns are still with us. Chifley envisioned responsibilities for a monopoly Commonwealth Bank that are an accepted part of the Reserve Bank's mission: stabilise the currency, contribute to full employment and encourage the economic prosperity and welfare for all Australians.

These fundamentals will likely survive Treasurer Jim Chalmers recently announced review of the Reserve Bank. Other things are dramatically different. The eight private banks that beat Chifley have shrunk to four big banks and the vibrant competition they promised is hard to find. In that era bank managers and customers knew each other and transacted business face to face. Farmers often said a good bank manager was worth two inches of rain in a drought.

Now the banks' relationship with customers is through distant call centres, computer-generated conversations, apps and internet portals. This separation and the banks' relentless drive for profits have created a culture that came under bruising criticism during the 2019 banking royal commission. In his final report, Commissioner Kenneth Hayne lashed the banks and outlined multiple recommendations to restore public confidence in the industry. Australians voted to save their banks in 1949.

Seven decades later it seems Australians have to be saved from their banks.

- Bob Crawshaw is a retired public relations executive and is researching communications campaigns that shaped Australia.