Mouldy homes our only option

Em Reid has big ideas.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

She runs a successful regional business, organises pop-up events with tattoo and beauty artists, and draws crowds of young people to the otherwise sleepy NSW town of Milton.

But Ms Reid is plagued by the fear of becoming homeless.

The 30-year-old owner of Blanc Space Tattoo Studio scrolls real estate websites for rentals daily, worried she may be forced from her South Coast village.

She's even considered purchasing a van to perch on her mother's property so she can stay local and keep her thriving tattoo shop and art gallery alive.

"We were in a really secure long-term rental but they wanted to renovate it and we had to move. We've had to move into a house with mould in it. I'm seeing this happen to everyone," she says.

Surfing the pandemic property price hike

Not everyone has a back-up plan and some leave town to find an affordable alternative or couch surf while they wait.

The pandemic house price boom and the mass exodus from capital cities to country and coastal areas have pushed lower-income earners out of their rentals.

The average weekly income on the South Coast - a popular holiday and weekender destination for Sydneysiders and Canberrans - is $941.

But mean rents have jumped from $450 to $653 a week in two years - an extra $866 a month for residents to keep a roof over their heads, property analysts SQM Research revealed.

Housing affordability in the region is at crisis point and Ms Reid says young people have few options.

"It's ridiculous that the government expects young people to dig into their super so that they can get a house and compromise on their future savings," she says.

Gig with no crowds

Ms Reid, who left her small town for the city when she was 18, knows she would thrive as a creative in the big smoke. But now she's back she desperately wants to stay.

Her tattoo studio draws visitors from across the country who funnel money into the town.

"Everything's happening in Milton," she says. "Local venues are hosting gigs and street festivals to make the region more attractive to young people.

"It's scary, because how do you expect to go out to a restaurant or see a gig if no one can afford to live here?" Ms Reid says.

Many businesses are still grappling with COVID-prompted staff shortages. And low ticket sales can lead to event cancellations.

The Deadly South, a community art organisation in Ulladulla, works hard to deliver a weekly local cabaret show.

Milton's Seeking Serendipity Bar & Kitchen hosts visiting drag queen performances from Wollongong.

"They do so much for the nightlife, but sometimes I feel they don't get the engagement they deserve," Ms Reid says. "There's so much potential, just not enough people to enjoy it."

Closed after dark

Most small regional councils don't appear to have night-time economy strategies like their regional city counterparts.

The Australian Local Government Association (ALGA) provided plans and policies for regional centres like Wollongong and Newcastle, but lacked national data.

There's so much potential, just not enough people to enjoy it.

- Em Reid, tattoo artist in Milton, NSW

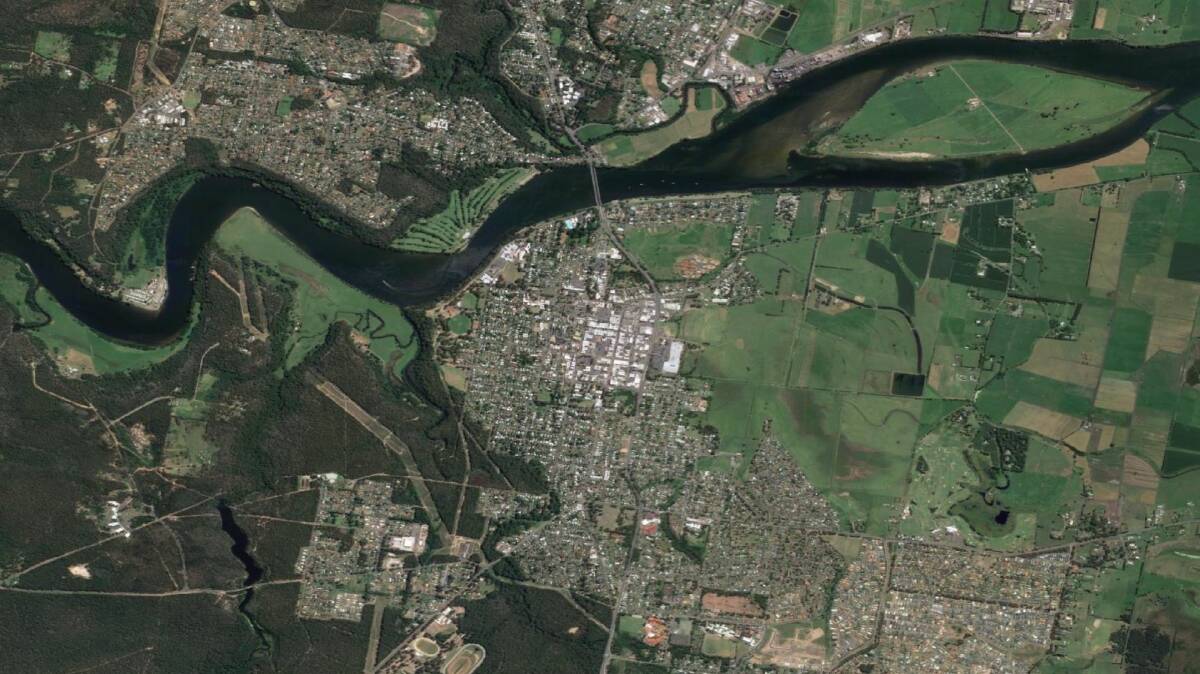

Shoalhaven City Council, which encompasses 49 towns and villages and covers a 4,500-square-kilometre area stretching from Berry to North Durras, could not pinpoint any schemes for the after-dark economy.

In 2020 there were an estimated 22,000 people aged between 15 and 34 living there, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

As the NSW South Coast is a tourist destination, the council does have plans to boost winery tours and specific events.

Uber lite

David Schofield is one of just five registered Uber drivers across the Shoalhaven, which stretches from Berry to North Durras.

The father of three, who lives in Nowra, has been taxiing people around for half a decade and has lobbied Uber to recruit other drivers.

The demand is high and he's exhausted.

"Before COVID we had enough drivers in Nowra and it was really, really good," he says.

"Then everyone stopped doing it - except me. And I can only do it part-time because I have kids and a day job."

His passengers are mostly young- to middle-aged people needing transport to and from local pubs, including the Bomaderry Hotel, Huskisson Hotel, and North Nowra Tavern.

"If there's more drivers they [would] get utilised so much more down here. I've constantly got work on," Mr Schofield says.

Early to bed

But he can't work as late as his customers would like.

"A lot of customers say they wish I was on later - from 11 o'clock to midnight. But I put their safety first. I try not to overextend myself, being one of the only drivers," he says.

"If we have more drivers, we would get a lot [more] people from point A to point B in the timeframe that they want. It would make accessing nightlife here easier."

Uber operates in 43 cities across Australia and has 3.8 million active riders.

The rideshare giant did not respond to queries about whether it planned to encourage more drivers in regional areas.

Uber says where there's demand for the service, it works to find drivers.

Asked whether it believed more drivers could boost regional economies, a spokesperson pointed to a 2019 report showing the service contributed to "a vibrant night-time economy in Sydney".

My story: Grace Crivellaro

Raised by a single mother in a regional town, I watched her work hard to provide for my brother and me. She sacrificed her weekends and often worked six days. We pitched in as soon as we were old enough. But I knew we were lucky because we had a roof over our heads.

At 25 I work full-time as a journalist in the Illawarra region of NSW. Before that I was based in the Shoalhaven to the south. A housing crisis is roaring through both of these areas, with people living in tents in caves.

I've interviewed hardworking people with full-time jobs who face homelessness. I can't help but worry for my generation - and the growing cohort of older people living on the edge of poverty.

Over the past two years I've moved house three times because landlords decided to sell or come home.