The regional Australian story

A decade ago when Charlotte* was nearing the end of school, thinking about a career and dreaming of one day owning her own home, the median value of properties in her region was about $313,000.

Subscribe now for unlimited access.

$0/

(min cost $0)

or signup to continue reading

Now she's in her mid-20s, paying $290 a week in rent, and struggling to scrape together a deposit for an average property now worth $561,000.

She takes home $60,000 as a full-time junior nurse. Groceries have risen four per cent in just three months. And, over the past year, petrol prices have leapt about 35 per cent.

Charlotte's weekly budget

- Take-home pay: $939

- Expenses: $290 rent, $112 petrol, $155 groceries, food, drink, $155 bills, $50 car repayments, $100 other (appliances, repairs, clothing, furnishings)

- Total expenses: $862 total

- Savings: $77

Charlotte is not a real person, but she's fairly average for a young person living in a large regional town in Australia's eastern states.

If she has no children, no out-of-pocket medical expenses, no pets, no other personal debt, no accidents or major illnesses, rarely if ever eats out, has few hobbies, and doesn't travel at all, she could save a maximum of $77 a week. If only.

But hypothetical Charlotte will eat into that $4,004 a year when she has to pay the insurance excess because her car's side mirror was knocked off.

She'll need to dip in again when she gets a cat for companionship, or when she visits her folks interstate, or when she needs physiotherapy for a netball injury or emergency dental work.

The haves and the have-nots

Communities across the nation are divided into the haves and the have nots - those who can absorb a 5.1 per cent annual rise in the cost of living and petrol above $2 a litre - and those who cannot.

"You've got about half the community that are doing quite well out of the price rises. It's the other half who are being badly affected," Regional Australia Institute (RAI) chief economist Dr Kim Houghton says.

"We're splitting between those who are homeowners, or have significant equity in their property, and those who have new loans with less equity, or those who are trying to get into the rental market.

"There's a split between the haves and have nots," he says.

Living on the brink

Young people like hypothetical Charlotte are the lucky ones. Tens of thousands are at risk of homelessness, especially Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, older women and people fleeing domestic violence.

Around 790,000 Australians lived in social housing in 2020-21, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Nearly 70 per cent of those were in public housing.

Although there was a very small rise in the number of social housing dwellings overall, the waiting list for public housing grew to 163,500 households, up 8,359 from the previous year.

Even where housing is available, regional Australia is often not suited to young workers. Apartments are rare and family homes are priced beyond the reach of single people starting out in their careers.

In the town of Muswellbrook in the Hunter mining region, nine in 10 dwellings are houses, data from property analyst CoreLogic shows.

The precarious housing market combined with cost of living pressures and the ongoing impact of the pandemic have created a "perfect storm", Youth Action chief executive Kate Munro says.

All of those things are creating a perfect storm of disadvantage for young people.

- Kate Munro, Youth Action

"All of those things are creating a perfect storm of disadvantage for young people.

"Young people are much less likely to have the capacity to enter into home ownership, which means they're in a rental market and the rental market in regional areas is tough at the moment," she says.

The 'rush to the regions' fallout

In Australia's expensive "bush capital" Julieann Bailey works full time but has been living in a caravan park tent with her husband, teenage son, and two dogs.

She's 25 minutes from The Lodge, the luxurious official prime ministerial home. But the median rent in Canberra was $684 a week in April, according to CoreLogic - beyond the reach of a minimum wage worker.

Regional Australia grew by 70,900 people in the 2020-21 pandemic year as city slickers fled crowded metropolises.

But home prices jumped 29.1 per cent to $800,300 in regional NSW in the year to March. They rose 17.4 per cent in country Victoria.

This is pushing young people further out from traditionally affordable regional centres and putting pressure on small towns with few services.

"That movement out of the city has pushed rental properties up so young people who are on those lower wages and are more likely to be employed casually ... it's really difficult for them," Youth Action's Ms Munro says.

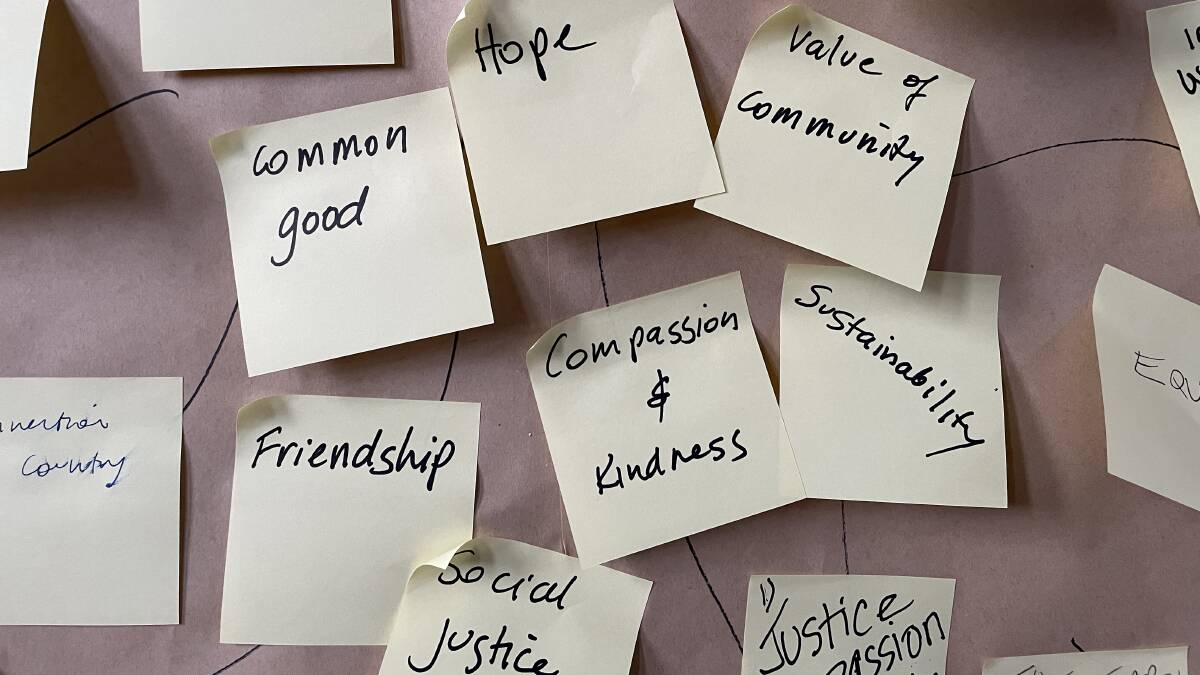

Communities forge their own solutions

Young people living outside capital cities are being pushed to their financial - and mental - limits.

But with energy and passion they are fighting to build a full, if frugal, life in regional Australia.

Affordable housing advocates like National Shelter say more social housing is needed to ease housing pressure.

Individual and community efforts still need to be matched by an increase in regional support services for young people, as well as an elevation of young voices in policy decisions, Youth Action says.

"It's really important that we include young people's voices in those discussions because it's very hard to get a sense of what things are like if you're not listening," Ms Munro says.

My story

My family of seven squeezed into a three bedroom house when I was growing up. As the eldest child, I watched my parents work hard to make ends meet. I remember when I was nine Dad started a lawn mowing business. Once we were old enough, my four siblings and I pitched in to help and spent most afternoons and weekends doing yard work.

These days, I consider myself one of the lucky ones. I work full time as a journalist and I'm paying a mortgage on a home with my partner in the NSW Central West town of Mudgee.

But, at 24, I worry for my generation. I've written dozens of stories about the regional rental crisis and spiraling cost of living. I've interviewed hardworking people who live under constant threat of homelessness, making every cent stretch further each week.

Across regional Australia this could be me. It could be your child or grandchild. It could be you.